Community Resilience through Water Security

- Dana Dopleach

- Mar 22, 2022

- 38 min read

A Guide to Replenishing Groundwater Supplies

March 2022 - Mercy Corps

Introduction

Most of the world’s freshwater is found below the Earth’s surface and is commonly referred to as groundwater. Groundwater is found in naturally occurring underground reservoirs or aquifers, which are subsurface bodies of permeable rock which can contain or transmit groundwater. In some regions, groundwater remains an undeveloped resource, offering promising opportunities for agricultural and domestic use. In other regions, land degradation, climate change and the overexploitation of groundwater has led to declining groundwater availability, contributing to food insecurity, disease, and conflict.

MAR & Mercy Corps

This guide will be particularly relevant to Mercy Corps programs in arid areas where groundwater is a critical source of water for households and productive use. Where land degradation has reduced the natural infiltration of rainfall, increasing the volumes and timing of runoff results in diminishing opportunities for storm flows to recharge aquifers. Increasing air and soil temperatures, lower and more erratic rainfall events and the increasing frequency and duration of droughts exacerbate the threat to groundwater supplies.

While particularly acute in arid regions, water scarcity is the product of water shortage and water stress and can threaten health and livelihoods even in humid environments. [1] Water shortage exists when the available water resources are limited in comparison to the needs of a population; water stress exists when levels of withdrawal or consumption of water are high relative to the timing of water availability. While climate and the physical environment drives water availability, population growth and usage levels drive shortage and stress. [2] Replenishing groundwater supplies is therefore an important tool for Mercy Corps teams as they engage in regional and local efforts to sustainably manage groundwater supplies.

For much of the 20th Century, meeting the increase in human demand for freshwater was achieved by building dams and reservoirs to capture river flows, storing this water above ground. While these structures have often created important benefits, they have all too often come at a very high price, particularly for the poor and marginalized groups.[3] Over the past sixty years, interest has grown in a variety of techniques for increasing the below ground storage of water.[4] More recently, Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR), has become the internationally used term to describe the complete range of physical tools and/or techniques involved in this process. The purposeful replenishment of aquifers is an alternative, sustainable approach to water storage. In very simplistic terms the purpose of the MAR approach is to slow down surface water and enable the distribution and percolation of this water into aquifers. By storing surface water underground, evaporation is avoided until such time as the water is needed and extracted. MAR techniques look to mimic and augment the mechanisms by which natural processes recharge groundwater.

This guide introduces the Mercy Corps’ Community REsilience through Water Security (CREWS) approach. The guide is divided into five parts. The first section reviews the challenges to managing groundwater sustainably. The second section provides an overview of the water cycle and hydrogeology and the science behind groundwater management. The third section introduces MAR and provides a guide to MAR techniques, using a series of explanatory graphics. The fourth section walks through the CREWS seven-step field and community-based assessment process provided by which Mercy Corps staff can enable communities to better understand and manage their groundwater supplies and engage in the development of a community groundwater replenishment project. Finally, the guide provides links to relevant documents and online information which can be used by Mercy Corps teams to further improve their knowledge and skills around MAR.

[1] Falkenmark, M. 1997. Meeting Water Requirements of an Expanding World Population. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 352, 929–936. [2] Kummu et al. 2016. The World’s Road to Water Scarcity: Shortage and Stress in the 20th Century and Pathways Towards Sustainability. Scientific Reports 6(30495). WEBLINK [3] World Commission on Dams. 2000. Dams and Development: A New Framework for Decision-Making. London: Earthscan. [4] Dillon, P. et al. 2018. Sixty Years of Global Progress in Managed Aquifer Recharge. Journal of Hydrogeology. WEBLINK

The Challenge of Groundwater Management

Overuse and declining groundwater quality, both caused by human activities, have resulted in significant degradation of many of the world’s groundwater resources. [1] In developed economies, regulations are often only imposed after the resource has been compromised. In part this results from the often-limited understanding of groundwater as a resource. As groundwater is invisible to the human eye and requires an understanding of an area’s subsurface physical environment trends in its condition are hard to observe. In the contexts in which Mercy Corps works, the lack of technical knowledge about groundwater and the pressures on groundwater resources are significant (see inset). Legal frameworks for regulating groundwater usage are often top-down and bureaucratic in nature, resulting in unrealistic expectations for developing and managing water allocations.[2] In addition, customary community water tenure systems are not recognized or poorly integrated in these statutory frameworks.[3] More often than not, existing regulatory frameworks for groundwater and their accompanying institutions are absent in rural areas in these countries, meaning that local collective action towards improved management is the only near term option. Fortunately, organizations like Mercy Corps can support local action by raising community awareness and capacity to manage surface and groundwater resources as a single interconnected resource.[4]

Threats to Groundwater

Groundwater resources are threatened by a combined effort of human activities and climate change. Population growth and increased consumption due to rising development levels are increasing groundwater extractions globally. In addition, human activities on the land surface, including compaction of soils and disposal of waste and effluent, limit natural recharge and result in the leaching of pollutants through soils, degrading groundwater quality. Climate change increases the frequency, severity and duration of droughts leading to an increased use of groundwater to maintain soil moisture necessary for agriculture and altering historic recharge patterns. Increasing global temperatures, declining annual snowpack, and melting glaciers, along with increasing dam storage are leading to impacts on annual river flows. In coastal communities, further pressure on groundwater extraction to meet human needs can also lead to saline intrusion in aquifers leading to the degradation of groundwater quality. The combination of these pressures on groundwater systems is worsening water insecurity.

[1] UNESCO. 2015. Global Agencies Call for Urgent Action to Avoid Irreversible Groundwater Depletion. Global Agencies include FAO, World Bank, UNESCO, and the International Associate of Hydrogeologists. Web Article found WEBLINK [2] Schreiner, B. and B. van Koppen. 2020. Hybrid Water Rights Systems for Pro-Poor Water Governance in Africa. Water 12(155) Web Article found WEBLINK [3] Rights and Resources Institute and Environmental Law Institute. 2020. Whose Water? A Comparative Analysis of National Laws and Regulations. Web Article found WEBLINK [4] Hardberger, A. and B. Aylward. 2021. Groundwater Governance for Conflict-Affected Countries. UNESCO I-WSSM. WEBLINK

Within Mercy Corps areas of operation, many of the challenges associated with improved natural resource management are found at the community level and thus require community-led solutions. This has prompted the development of our CATALYSE approach to sustainable project development. This approach involves community members in program design and implementation promotes their ownership over decision-making and builds their knowledge and skills to carry out those decisions. CREWS is intended to be a community-based approach and thus should be used in conjunction with Mercy Corps CATALYSE approach to community engagement.[1]

However, this guidance note is not about top-down governance of groundwater, nor about the intricate mechanisms of self-governance of groundwater (see box below). Rather, it addresses the very practical question of how Mercy Corps and communities can collaborate to identify and then implement proactive interventions that replenish groundwater supplies, while also addressing several interrelated problems: (1) changing patterns of rainfall from climate change, (2) declining recharge rates due to ongoing land degradation and (3) growing demands on limited supplies. All with the objective of improving seasonal and long-term water security in a sustainable and equitable manner.

The problem of governing groundwater

In Hardin’s classic 1968 paper “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Hardin defines a “common” as a natural resource shared by many individuals.[2] In the absence of a collective responsibility to manage the resource and its use, individuals tend to exploit the commons to their own advantage, typically without limit. This results in the tragedy of the common “pool” being depleted and eventually lost or severely degraded. Since Hardin’s paper was published, our understanding of this “tragedy” and the management challenge posed by what are now called “common pool” resources has greatly evolved due to advances in political scientists’ understanding of traditional common property regimes and how collective action evolves or can be engendered to address common pool problems.[3] Meanwhile, natural resource economists have greatly expanded our ability to diagnose the market failure expressed in Hardin’s argument.[4] This political economy approach can be used to better understand and design institutional arrangements and incentive structures to address the many public good problems faced in water resource management, including those around the commons management of groundwater.[5] Despite these advances in our understanding of how to improve management of common pool resources, globally, groundwater continues to resemble this tragedy of the commons scenario more closely than one of efficient and equitable use.

[1] Mercy Corps. 2018. CATALYSE: Communities Acting Together. A Governance in Action Guide. [2] Hardin, G., 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Nature, 162, 1243-1248. [3] Ostrom, E. 2010. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Nobel Prize Lecture. WEBLINK [4] Randall, A. 1983. The Problem of Market Failure. Natural Resources Journal. 23: 131-148. [5] Aylward, B. 2016. Water, Public Goods and Market Failure. Portland: AMP Insights. WEBLINK

Catchment Hydrology and Groundwater

To understand MAR, a basic understanding of catchment hydrology and groundwater systems is required.[1] This section presents the basic terms and principles that will be employed in the remainder of the guide.

Figure 1. Map of the Nile River Basin in North Africa (Sourced from Springer)

Catchments. A drainage area is simply the land through which water drains via gravity to a single point. A catchment (or watershed) therefore is often considered as the area of land from which water drains (or is collected) into a single stream or river, down to its confluence with another such waterway. Catchments can range in size from exceedingly small (i.e., a few hectares) to exceptionally large. Larger catchments that drain to the sea, or an interior terminus, are often called basins. For example, the Nile River Basin (see Figure 1) traverses a vast proportion of the African continent and flows through more than 10 countries from the mountain regions around Lake Victoria to Egypt’s Nile delta, where it flows into the Mediterranean Sea.[2]

The Water Cycle. The constant movement of water through a catchment is driven by meteorological and hydrological parameters and processes (see Figure 2 which provides a depiction of the intersection between the water cycle and the groundwater system). This water cycle begins with the condensation of atmospheric moisture into precipitation (rainfall and snow), which falls to the land surface. A portion of precipitation is lost as it is intercepted by vegetation and evaporated back into the atmosphere. Additional water is lost to the atmosphere through transpiration to fuel plant growth and maintenance and from the evaporation of water from soils and land surfaces. These losses are referred to jointly as evapotranspiration. The water from precipitation that is not lost to evapotranspiration becomes runoff as it accumulates across the landscape as overland and sub-surface flow. This water flows downhill eventually entering streams, rivers, wetlands, and lakes. These visible waterbodies are denoted by the term surface water. Surface water flows on out of the catchment to the sea, or to the waterbody in the lowest point in a land-locked catchment (called a terminal lake).

[1] Note that in American English the term “watershed” predominates, whereas in British English the term “catchment” is used. [2] As drainage areas are often nested one within the other as stream and river systems come together, there are local conventions in which these catchments are numbered in sequence as they nest, so that for instance the Nile Basin would be a 1st order catchment and the catchment of the Blue or White Nile would be a 2nd order catchment.

Aquifers. A portion of the rainfall falling in a catchment naturally percolates through the surface soils into the underlying groundwater system. Groundwater bodies that hold accessible water are called aquifers. There are two types of aquifers, unconfined and confined. An unconfined aquifer is an underground body formed from water infiltrating under gravity to a zone of saturated soils beneath the land’s surface. This unconfined aquifer’s upper surface is open to the atmosphere and is commonly referred to as the water table. A confined aquifer typically lays below an unconfined aquifer and resides beneath an impermeable layer of soils or rock that acts to restrict or reduce the movement of water either in or out. The rate at which water infiltrates into an aquifer will depend on the types of soils and their condition, and the underlying geologic materials. Figure 2. Schematic of the water cycle and groundwater within a catchment Water moves both in and out of aquifers and these processes are called groundwater recharge (in) and groundwater discharge (out).

Figure 3. Schematic depicts the timing and movement of groundwater through aquifers as it relates to the recharge and discharge processes

Recharge and Discharge. Unconfined, shallow aquifers can be recharged more easily from precipitation and surface waters, making the seasonal replenishment of them more accessible, assuming that the wetter seasons are sufficient in amount of rainfall and duration. As movement of water through an impermeable layer can be severely limited, or at best a very slow process, confined aquifers can have a more limited connection to surface recharge from rainfall as shown in Figure 3. The movement of water recharged from rainfall through the subsurface can therefore range from being reasonably quick (days to years) through to taking much longer (centuries to millennia). When groundwater is pumped at rates that exceed the timing of these natural recharge processes, it often leads to declines in groundwater storage and supplies which leads to human interventions such as MAR.

Discharge from groundwater results from a combination of the downgradient movement of groundwater in a catchment and/or the intersection of impermeable layers and the surface, exposing an aquifer and allowing the water to flow into surface waterbodies. Natural springs that bubble up out of the ground are a common visible example of groundwater being discharged. However, a vast majority of discharge is unseen, being contributed incrementally along the lengths of rivers and streams as a river moves downgradient in a catchment.

Surface water flows and groundwater recharge and discharge can be responsive to changing weather conditions. The timing and volumes of flow in surface waterbodies in most water scarce catchments can be typically driven by seasonal weather patterns. Wetter seasons typically result in higher flows in rivers from overland flow and runoff. During the drier, hotter months, rivers may continue to flow (perennial rivers) or dry up (ephemeral rivers). When rivers continue to flow during long dry periods this is driven by groundwater discharge and is called baseflow. Groundwater discharge is highly dependent on the amount of water being stored in the aquifer and the aquifer’s physical properties. Using a garden hose as an analogy, the water coming out the bottom of the hose is driven by the rate at which water is pushed into the top of the hose. If the natural rate of recharge decreases, for example, due to climate change and decreases in rainfall, then the rate of discharge and baseflow will decrease over time. Similarly, if aquifers are being depleted or ‘mined’ from human usage faster than they can be recharged naturally, the results are measured in reductions in a longer-term diminishment of baseflow to surface water bodies and/or decreased flow or drying up of springs. Changes in groundwater levels in an unconfined aquifer or the pressure in a confined aquifers indicate if a groundwater resource is being ‘mined’ or replenished on balance.

Surface vs Ground Storage. In a vast majority of catchments, the demand for water (during drier, hotter months) does not correspond with the supply of water (during wetter, cooler months). To meet human demands at times when they exceed the natural supply, water must be captured and stored. Surface storage in lakes and wetlands represent are a natural form of storage. Built structures such as dams or ponds are a way to augment this storage. However, built forms of surface storage pose several challenges, including evaporative losses, detrimental environmental impacts of blocking waterways, the ready availability of engineering expertise and construction materials, high construction costs, and the need to distribute the stored water to more distant use areas. Dams are also well-known for increasing societal conflict due to disparities in access to the stored water, or the services it provides such as hydropower. Storing water underground has the distinct advantage of little evaporative losses; aquifers tend to be naturally distributed spatially which provides more equitable access through the drilling of boreholes. Groundwater storage development can also be significantly less expensive than surface dams due to the reduced costs of infrastructure, land acquisition, and water distribution costs.

Groundwater Quality. Groundwater quality is of great importance for human potable supplies. Unconfined aquifers are more susceptible to contamination from surface activities. Their relatively shallow depth allows boreholes (or wells) to be easily constructed, but also means they are more susceptible to contaminants leaching from agricultural, industrial and/or wastewater activities into unconfined aquifers and causing illness, disease and even death. Confined aquifers, which are typically deeper, are separated by more impermeable layer(s). These layers can help protect confined aquifers from contamination but subsequently can be more difficult to restore if they become contaminated. Efforts to increase groundwater storage through MAR need to ensure that both the recharge water is of higher quality and that the protection of the current users is prioritized. Recharging cleaner water can be used to help improve groundwater supplies using MAR when combined with efforts to also reduce the sources of the existing contamination.

Groundwater Mining. Accessing confined aquifers often requires deep boreholes, which can be costly, or drilling techniques and materials that may not be available locally. Deep, confined aquifers are said to contain fossil groundwater (or groundwater reserves), indicating that this water was stored in the aquifer a long time ago, when the geology of the area may have been quite different. As with the extraction of oil (or other fossil fuels) the implication is, that extraction of this water on a human time scale cannot be sustained, as it depletes water that was stored over a geologic time scale (e.g., millions of years).

Groundwater and Ecosystems. Environmentally, aquifers play an important role in providing baseflow to streams, rivers, and springs on which aquatic ecosystems depend. These ecosystems provide sustenance and a source of livelihoods to humans. Groundwater dependent ecosystems are generally defined as either surface or sub-surface aquatic ecosystems which are dependent on the availability and quality of groundwater. The systematic depletion of groundwater reserves through mining of deep aquifers and the over-pumping of shallow aquifers has been shown to have direct and detrimental impacts on the health and survival of aquatic organisms. Beyond the obvious dewatering of natural springs, issues caused by groundwater depletion include decreased baseflow in streams and rivers during the drier, most critical summer months; increased water temperatures and loss of thermal aquatic refuge for species from cooler groundwater in-flows, and lack of higher quality groundwater to dilute the concentration of contamination from surface runoff.

Water Balance. The water available in every catchment is governed by the interconnected processes summarized in a catchment water balance (or water budget). In simple terms, this balance is an accounting of all the water entering a catchment relative to all the water leaving a catchment. Precipitation is the primary source of water entering catchments. Evapotranspiration losses along with outflows in rivers and groundwater are the primary sources of water exiting a catchment. Nested in this water balance is water stored in the catchment, including in soils, lakes, reservoirs, and groundwater. Environmental change and human interactions with surface water and groundwater will alter this water balance. MAR is one of these human interactions which can be used to replenishment and augment natural recharge processes. As stated earlier, MAR techniques are used to capture surface water during the wetter periods and store it in aquifers so that it is available during dry seasons or droughts for beneficial use. Beneficial uses will vary by catchment and community from irrigation for agricultural, drinking water supplies, or environmental restoration and augmentation of ecosystem services, to maintaining cultural values or practices that are important to the community, such as fishing or other forms of food gathering. In terms of the water balance, MAR acts to limit the surface losses from a catchment and, through the slowing down and detention of water, an increase in the amount stored in groundwater. As such MAR is a tool for rerouting and reallocating the available water budget in a catchment to meet human and environmental needs.

Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR)

A MAR project represents an investment in improving groundwater storage. It therefore requires a clear goal, an understanding of the context, and the identification of specific techniques for achieving replenishment. Once the goal is established, the specific context – in terms of catchment hydrology, groundwater system and water supply needs – will dictate the type and complexity of MAR techniques required. The desired scale will also influence the chosen approach as MAR is a flexible tool that can be scaled from small sub-catchment areas which support dozens of people, through to regional scale implementation that can supply whole towns, cities, and even countries. In this section, the goals, questions and techniques involved in designing a MAR project are presented.

The Goal of MAR

MAR is the purposeful recharge of surface water into groundwater aquifers. MAR supplements naturally occurring recharge to compensate for community groundwater usage. MAR, when applied with the goal of improving water security and supplies for communities in the developing world, should seek to increase recharge to achieve a sustainable yield. Figure 4 provides a graphical summary of inputs (recharge) and outputs (discharge) that are involved in balancing groundwater storage. Groundwater storage is restored, maintained, or improved by increasing MAR activities enough to offset the current or anticipated uses, thus resulting in a more sustainable yield. In some cases, improved replenishment of groundwater can result in additional yields being available to communities.

Previous community-level MAR efforts have shown that MAR programs are most effective when they begin with a demonstration project. Tangible results from these demonstrations often provide the ‘proof of concept’ required for local stakeholders and leaders to build the momentum required to continue the development of a groundwater replenishment strategy. Additionally, these projects can provide useful information about the technical properties of local aquifers and which techniques may be best suited to local conditions. Developing these demonstration projects is the primary purpose of this guide.

Basic MAR Questions

Before MAR project techniques and tools are selected, three primary questions should be considered:

· What type of aquifer recharge is being considered? (e.g., shallow unconfined, deeper confined, etc.)

· What are the specific characteristics of source water being used for recharge? (e.g., timing, quality, rates, etc.)

· What are the intended beneficial uses of that recharge water? (e.g., human drinking water, irrigation, etc.).

Starting the assessment process with a clear understanding of these considerations forms the foundation of any groundwater replenishment program. The answers to these questions determine the basic viability of any given MAR project, help to identify potential opportunities and risks, and point towards the types of MAR techniques that will deliver the desired result.

What Type of Aquifer Recharge?

The type of recharge mechanism used for a project is strongly dictated by the type of aquifer being targeted. As discussed in the previous sections, aquifers can range from unconfined to confined based on the subsurface geologic framework in which the aquifer(s) resides. The two primary recharge mechanisms relative to an aquifer’s confinement are:

Infiltration – where water is percolated from the land surface to an underling water table of an unconfined aquifer. These aquifers tend to be shallower and can be recharged using techniques like infiltration basins, which are relatively inexpensive and easy to maintain.

Injection – where water is directed via a constructed structure (e.g., injection well) past a confining bed and/or targeting a deeper, more confined aquifer. Injection techniques tend to be more expensive and require more maintenance (e.g., periodic back flushing of the borehole) than infiltration techniques. Injection techniques can range in mechanism from passive (using gravity) to proactive (pumping into aquifer).

Generally, infiltration MAR techniques have the advantage of being easier to design, build, and maintain, often requiring simpler surface excavation work to form trenches, basins, or pits that can be constructed using commonly available excavation labor and equipment. Infiltration has the added benefit of often being easier to maintain for issues such as surficial clogging. The percolation of water through the soils can also be used to help improve or “polish” the source water before it enters an aquifer. The periodic wet and dry cycling of infiltration sites coupled with the removal of any accumulated silts can help maintain infiltration sites.

Injection techniques can also be simple to implement (e.g., excavation through a labourshallow confining layer to allow easy recharge access) but generally require more advanced hydrogeologic knowledge and can require more specialized construction techniques (e.g., drilling rig) than can be sourced locally. Injection projects also often require special considerations around source water quality. Injection water quality improvement techniques (e.g., filtering through a wetland) may need to be considered during the project design process. In the end, selecting the appropriate recharge technique is a matter of finding the “right tool for the right job.”

What is the Source of Water?

The next important consideration for developing MAR is the source of water that is intended to be used for the recharge activity. The evaluation of the source water should include a sound understanding of its quantity and quality. The quantity of source water is reliant on the timing and rates/volume of the source water (from rivers, streams, lakes, etc.) which is often predicated by the seasonal weather patterns in a catchment. In some situations, the wet season and high rainfall events will be the primary times when water is available for recharge.

These events may also increase runoff across the surface of the land, which can impact the quality of the source water. Contamination from human or animal sources of fecal pollution are of particular concern when planning a MAR project where the goal is potable groundwater supplies. Contaminates found in source water could range from nutrients, such as nitrates from agricultural fertilizers, to more toxic substances, like heavy metals that can leach from upstream mining or industrial activities.

The timing, quantity, and quality of the source recharge water coupled with careful design considerations can be used to overcome many of these kinds of challenges. For example, a pond can be constructed where source water is diverted and retained to allow sediments to settle. Improved quality source water can then be directed to a MAR site for recharge without the risk of operational maintenance issues. Therefore, it is especially important that a clear understanding of the potential source water quality risks be evaluated as part of the planning for any MAR project.

What are the intended beneficial uses of groundwater?

The last of the three primary MAR planning considerations are the intended beneficial uses of the recharged water. Projects intended to provide water for irrigation might be developed quite differently than projects intended to supply clean drinking water. Similarly, groundwater access points (e.g., community drinking water boreholes) may also help to define potential MAR locations. For example, rooftop rainwater harvesting, and local, focused recharge proved to be the most effective MAR techniques in urban India. In contrast, recharge in the more distant, upper parts of a catchment can help distribute recharged water across rural areas via spring-fed streams and rivers. Fundamentally, community engagement is critical to identifying likely beneficiaries and beneficial uses, which is consistent with the Mercy Corps CATALYSE engagement strategy.

The Tools of MAR

Following the evaluation of the type of aquifer(s) being targeted, the source of recharge water, and the intended beneficiaries, there are a wide range of tools that can be considered for application in a MAR project. These tools cover the spectrum of applications for the three primary MAR criteria and the two general categories of MAR: infiltration and injection.

Types of Managed Aquifer Recharge - Infiltration Techniques

Bank / Soil filtration from surface

In bank or soil filtration, groundwater is extracted from a well, borehole, or infiltration gallery near or under a surface water source (e.g., rivers, canals, or infiltration basins). The process of the water moving through the soils or sands helps to remove contaminants and sediments from the water. Recharged water is recovered from a pumping well which helps to induce infiltration from the surface water body. The water quality is more consistent as the filtration process works to reduce sediments and pollutants found in the surface water. Examples are commonly found Europe, and a relevant example comes from India, which focuses on improving water quality for drinking water supplies.[1]

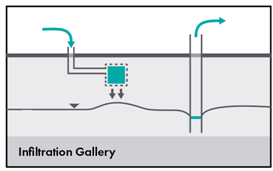

Infiltration galleries

Infiltration galleries are often utilized when land availability is limited such as in urban or industrial areas. They are often constructed in elongated grids of slotted drain tiles or pipes and laid into a permeable media such as sifted sands and gravels. They can help water infiltrate through the unsaturated zone to an unconfined aquifer or specifically to direct recharge past a shallower impermeable layer. An example is at Floreat Park, Western Australia.

Water Recycling using Soil Aquifer Treatment

Water Recycling is becoming a growing area of interest, particularly in urban areas were wastewater and stormwater are available. Soil Aquifer Treatment (SAT) is a well-documented alternative to modern treatment technologies (or complement) in which the natural filtration of source water through the soils helps to ‘polish’ or improve the quality of the water recharging the groundwater system by removing nutrients and pathogens.[1] In some examples, using wet and dry cycling of infiltration basins helps to maintain the recharge rate efficiency of these types of MAR projects. Mixing of native groundwater coupled with the increased residence time of the recharge can help to further polish the water for future human consumption. This filtration is especially useful after major flood and rain events, as these events often expose source water to fecal bacteria carried by eroded soil. Whilst SAT has mainly been evaluated for the use of wastewater for MAR projects, its principles are applicable to rural, developing world catchments where the ability to pre-treat surface water cannot be achieved due to the sheer costs and infrastructure required. Whilst water recycling and use of SAT is a growing technique around the world, likely the longest operating (early 1900s) program in the world is the Groundwater Replenishment System in Orange County, California.[2]

[1] https://sswm.info/water-nutrient-cycle/reuse-and-recharge/hardwares/recharge-and-disposal/soil-aquifer-treatment [2] https://www.ocwd.com/gwrs/

Infiltration Basins or Trenches

Infiltration basins or trenches are usually constructed at some distance from the source waterbody to help increase net recharge to an underlying unconfined aquifer. As rivers tend to be good natural mechanisms at recharging unconfined aquifers, it is common practice to locate infiltration basins outside the river’s influence and perpendicular to the groundwater flow direction. The removal of the overlying less permeable native soils and “ripping” or excavation of the underlying materials to break up any confining beds can help to increase the overall recharge rates at infiltration sites. The dry and wet cycling of basins and trenches can help maintain overall performance and avoid clogging. In the right geologic unconfined conditions, these infiltration techniques can achieve some of the highest recharge rates. When spatially distributed from the upper to the lower catchment, these MAR techniques can help to divert and slow water moving quickly through a catchment and recharge groundwater over larger areas. Increased groundwater storage across larger catchment areas can lead to improved groundwater storage for non-human water usage and contributes to downgradient improvements in aquatic ecosystem health and increased baseflows. Basins and trenches are also commonly used in Flood-MAR projects (covered at the end of this section) because of their relatively low cost of construction. These trenches also provide the added benefit of helping to reducing soil erosion by capturing overland flow during extreme rainfall events. These types of MAR projects are probably the most common worldwide, with India installing thousands of basins and trenches across many rural catchments.12 Examples of infiltration basins used as part of groundwater storage systems can be found in Abu Dhabi,[1] Spain,[2] and in Ethiopia.[3]

[1] https://gripp.iwmi.org/natural-infrastructure/water-storage/a-strategic-water-reserve-in-abu-dhabi/ [2] https://gripp.iwmi.org/natural-infrastructure/water-storage/the-alcazaren-pedrajas-managed-aquifer-recharge-mar-scheme-in-central-spain/ [3] https://gripp.iwmi.org/natural-infrastructure/water-retention-3/898-2/

Sand dams

Sand dams are built in ephemeral stream or seasonal sandy river channel beds in arid areas which have low-permeability bedrock. These dams are constructed atop bedrock to capture sands mobilized by high flow and flooding events. As sand accumulates behind the dam structure, water is trapped in the sands, providing an artificial aquifer that stores water that is less susceptible to evaporative losses. These aquifers are typically accessed via constructed wells during the drier seasons and may provide stock and potable water supplies. Unlike the other types of MAR discussed, this approach is designed to ‘create’ an artificial aquifer in which water can then be captured and stored. The area of benefit is dictated by both the volumetric capacity of the artificial aquifer and its ability to hold that water (leaking) during the drier seasons. Examples can be found easily found online, but a specific case study can be found in Kitui, Kenya.[1] Note there is a recent technical review paper on Sand Dams that is worth considering as it highlights the importance of a range of factors including water quality, and community health and wellbeing.[2]

[1] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frwa.2021.651954/full [2] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frwa.2021.651954/full

Recharge Releases

Surface storage dams on ephemeral waterbodies act to hold a proportion of water during flooding and wetter seasonal flows. Downstream recharge releases dispense this stored water via natural or artificial channels to improve downgradient aquifers and maintain environmental flow. Coupled with a progressive dam management plan, these projects can also help to provide source water to other downgradient recharge projects. This technique has the additional benefit of helping to manage potential clogging via the frequent re-working of the channel bed materials. Recharge releases are used all over the world (rarely called MAR). A recent article summarizes their use (along with a range of the other MAR tools) in Gulf Countries in the Middle East. [1]

Types of managed aquifer recharge - Injection Techniques

Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR)

ASR involves the injection of water into a borehole for storage and later recovery. Borehole construction can require specialist drilling and well construction techniques. ASR also requires pumps to recover the recharged water for use. ASR systems are commonly developed for confined aquifers, but this technique can also be used in unconfined systems, including to directly recharge water into much deeper water tables. Aside from infiltration basins, this is probably the most common type of recharge for a wide range of beneficial uses. ASR is commonly used by larger water users such as municipalities, industries, and for agricultural irrigation needs. ASR is likely to be more expensive than other types of MAR. Examples are found all over the world, including Abu Dhabi[1] and for major municipalities in water stressed areas such as the suburbs of Adelaide, South Australia.[2]

Aquifer Storage, Transport and Recovery (ASTR)

ASTR involves injection of water into a borehole for storage and recovery from a different borehole or group of boreholes. These systems are used to provide some additional water treatment as the water moves through an aquifer. Additionally, ASTR systems are used in community MAR projects where groups of well owners come together to operate a single ASTR site for the common benefit of many aquifer users. A good example of an ASTR borehole is on New Zealand’s North Island, in Gisborne’s coastal Poverty Bay Flats – Makauri Aquifer.[3]

[1] https://gripp.iwmi.org/natural-infrastructure/water-storage/a-strategic-water-reserve-in-abu-dhabi/ [2] https://www.jstor.org/stable/26151885 [3] https://www.gdc.govt.nz/council/our-projects/managed-aquifer-recharge-trial

Dry or Vadose Zone Wells

Dry or vadose (unsaturated) zone wells are typically shallow wells in areas with deep water tables and/or soil profiles that exhibit some confinement properties which inhibit infiltration techniques. These wells allow infiltration of high-quality water through a confining or semi-confined layer or deeper into an unsaturated zone to then recharge the aquifer at depth. A good case study example comes from India.[1]

Rainwater Harvesting

In rainwater harvesting, roof runoff is diverted into a well, sump, or caisson filled with sand or gravel and allowed to percolate to the water table. Water is then typically collected via pumping from a well. Examples are common around the world, with Indian government agencies actively encouraging rainwater harvesting in both rural and urban settings. A 2014 summary of rainwater harvesting across different agro-climatic regions in India is also a useful guide.[1] There is also a case study in the United Kingdom which has a comprehensive (commercial) summary of different applications of rainwater harvesting case studies.[2]

Other types of managed aquifer recharge

Ag-MAR

Agricultural MAR or AG-MAR is a relatively new term for a practice that has been used for thousands of years. It encompasses flood irrigation practices that seek to divert available water and flood whole fields to increase soil saturation and, eventually, agricultural production. The incidental recharge (water that percolates through the soils to the aquifer) provides benefits to aquifer storage. In the past 50 years or so, efficient irrigation techniques have been implemented, helping to spread limited water supplies across larger areas. However, a downside to these water conservation practices has been that less incidental recharge has occurred. Ag-MAR has hence become a more recently developed term as modern agricultural practices are adjusting to couple both water use efficiencies with recharging groundwater in rural catchments. AG-MAR is suitable for some crops but is detrimental to others. This technique has the advantage of not requiring extensive infrastructure, and it is spatially positioned to benefit the aquifers adjacent to relevant agricultural areas. Examples of this can be found in California and in Japan.[3]

Flood-MAR

Flood-MAR is also a relatively new term applied to MAR projects that capture peak flows in rivers and streams and redirect them into aquifer recharge.[4] The purpose is to both reduce the damaging effects of flooding, soil erosion, and sedimentation, and to help capture and recharge aquifers during high flow events. This MAR technique is attracting increased interest as climate change produces more severe and frequent flood events. This technique can be used in concert with many MAR techniques, but it is reliant on designing the MAR sites to manage the higher sediment loads and clogging potential associated with flooding. A long-standing example of capturing flood flows is found in Nebraska, USA.[5]

[1] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276271522_Urban_Rain_water_harvesting-_case_studies_from_different_agroclimatic_regions/link/55543dc508aeaaff3bf1b478/download [2] https://rainharvesting.co.uk/case-studies/ [3] https://gripp.iwmi.org/natural-infrastructure/water-storage/incentivizing-groundwater-recharge-through-payment-for-ecosystem-services-pes/ [4] https://gripp.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/01/GRIPP-Case-Profile-Series-Issue-4.pdf [5] https://gripp.iwmi.org/natural-infrastructure/water-storage/managed-aquifer-recharge-mar-in-nebraska/

Figure 5. The tools of MAR applied to various aquifer conditions and water usage needs

As outlined above there are a wide variety of MAR techniques and new approaches continue to be developed and refined. While techniques should be fit-for-purpose, no one project or technique will necessarily fulfil the need for groundwater replenishment across a catchment. Instead, a range of MAR techniques may contribute to groundwater management objectives across a catchment and across aquifers, as shown in Figure 5.

CREWS: A Community-Led, Science-Informed Approach to MAR Projects

A Stepwise Process

The CREWS approach provides a framework to assist Mercy Corp staff in envisioning the development of a community-based groundwater recharge project. This stepwise approach helps collect key information and identify any significant opportunities and risks that need to be considered and mitigated as part of a typical project’s development. This framework specifically incorporates the community and program participants into the process, recognizing the need to collect local knowledge and customs, understand water needs and usage, and build local support for any project going forward.

Communities often have highly relevant knowledge of local hydrology and groundwater resources in their catchment. It is important to incorporate this knowledge into the pre-implementation research as it will help build the foundations of the technical evaluations and ensure that the projects are fit-for-purpose.

The stepwise approach outlined immediately below and explained in this section, provides a general outline of the most important scoping needs for a MAR project. The steps and the information gathered coupled with common sense should help provide a basic understanding of the opportunities for MAR in each community or catchment. Even if more advanced project support is required (e.g., design engineering, borehole drilling, etc.) these steps will provide the information required to develop a project that will increase community water security.

Step 1: Assessment of the Catchment

This first step requires the project team to consider the wider catchment in which a community resides and to understand the fundamental hydrology, water cycle processes, human and environmental uses of water, and other key parameters to evaluate the need or feasibility of a MAR project. This process should be conducted in conjunction or quick succession with the community engagement (Step 2). In particular, the upgradient conditions (the source of water), downgradient conditions (aquifer), and intended beneficiaries need to be clearly established. During this step, basic information is collected to identify significant risks or challenges that need to be considered before moving forward. A mapping exercise that works alongside community participants (see Engaging the Community), is an excellent, collaborative way to help define the catchment boundaries, sources of water, groundwater areas of interest, local boreholes or water usage access points, and any other critical infrastructure, and environmentally or culturally sensitive areas (e.g., Location of areas where contamination may influence source water or the aquifer).

Step 1 should include collecting information on the following features:

a. Define the catchment boundaries, map topography including gradients and major hydrologic features, and conduct a water assessment of the catchment. A catchment map may already be available via online mapping repositories. Alternatively, free online resources, such as Google Earth, have aerial photographs, estimates of elevation and measurement, and mapping tools to help define the catchment.

b. Define the key biophysical parameters in this catchment: rainfall amounts, intensities and seasonal patterns, types of soils, quality of water, and any key ecological and cultural values that will be important to the plan.

c. Collect any available information on rainfall, evapotranspiration, flows and drought/flooding for the catchment. This can often be used to generate an indicative water budget for your catchment and help to further scope the project relative to the timing and volumes of source water that may be available for MAR. Take note that whilst exact flow measurements may not be available, qualitative descriptions on seasonal weather patterns, width/depth of rivers during high flows, and visual signs of water quality (clarify) are all extremely helpful foundational information for a project.

d. Define the desired usage of recharged groundwater, including human and ecosystem uses and local water users (community members and groups).

e. Understand the local aquifer structure (confined or unconfined, shallow, or deep) using existing boreholes and geologic materials found within them (e.g., clays/silts, gravels/sands, or mixtures). During this process work with a local champion to collect key facts about groundwater from as many project areas as possible, including the well depth, location, and seasonal changes to quality and quantity.

f. Assess the specific intended benefits of the MAR project relative to total water usage in the target area and community. This is particularly relevant to determining spatial location, timing, and likely aquifers that may be targeted with MAR.

g. Assess the water quality of the source and receiving groundwater using all forms of available quantitative (i.e., scientific measurements) and qualitative (i.e., interviews with community) information. Quantitative information sourced from laboratory or in-field testing is strongly preferred, but general knowledge from the local community will often be sufficient to assess the potential for any given project. Water quality is a pivotal consideration for projects particularly if they are intended to provide drinking water supplies.

h. For both Step 1 and Step 2, the guide strongly encourages the collection of photographs of all the existing water infrastructure, natural environment (e.g., river channel), and other relevant information. This is particularly useful when only qualitative information is available about these features, as it will provide a basis on which any further stages can be determined.

RISKS & Technical Issues

Risk is a major concern in the development of any water project; MAR is no different. Risks to human health, flooding, failing the communities’ expectations, poorly designed infrastructure, over-engineering, and lack of support from the community can all influence success. Mercy Corps encourages country teams considering a MAR project to deploy the fundamentals provided in the CATALYSE approach for community outreach and engagement in following these guidelines. Teams should also reach out to the Technical Support Unit to ensure that they have access to the requisite hydrogeological advice as they step through the process outlined here.

Step 2: Engaging the Community

“Today’s water problems cannot be solved by science or technology alone. They are instead human problems of governance, policy, leadership, and social resilience.”

— 2015 Stockholm Water Prize Winner Rajendra Singh – Rainwater Harvesting to Enhance Groundwater Security and Improve Community Resiliency

Mercy Corps has developed the CATALYSE approach to help guide working with local communities. This MAR guide defers to that approach for specific engagement strategies and notes that this step of the project is vital for the development of a MAR project or groundwater replenishment system. Identifying local champions or leaders that embrace and support the project also greatly helps to ensure that the project can progress. Successful, local community interest and involvement are critical to the maintenance and, ideally, expansion of MAR projects. Many MAR projects are not necessarily sufficient in scale to ‘fix’ a community’s groundwater water security issues by themselves. Empowering the local community with the tools and knowledge to replicate or expand the MAR project or engage in companion efforts (e.g., water conservation) should be a key goal of any demonstration or initial MAR project.

Integrating MAR project design to consider other related community needs such as flood management or reducing soil erosion should also be part of the community discussions. Other Mercy Corp guides such as the Resilience Design (RD) in Smallholder Farming Systems[1] also include techniques and practices that can complement MAR projects for specific beneficial uses and incorporate groundwater security into resilience programming.

In addition to these guides, there are several reasons that community engagement remains a key step in any MAR project’s development including:

a. Water is a treasured resource to communities all over the world. Water is often associated with cultural values and beliefs that are important to understand and incorporate into the conceptualization of a MAR project. These values are often particularly important for poor and marginalized groups and individuals in a community. Getting this part correct may be more important in determining feasibility than the technical and physical settings of a MAR site.

b. Identifying the way that a community accesses and utilizes groundwater is essential to ensure that any MAR project is going to help (not hinder) the resources. The diversion of water from a stream may also have downgradient effects on other communities, whose needs should also be considered.

c. Getting community ownership of the project is critical as the project requires a local presence for all the project phases. Ideally, community leaders or designated champions help generate ownership of the project and help to ensure its success going into the future.

d. A community mapping exercise should be a part of the first steps to understand a MAR project and is highly recommended.

e. Local input is essential to clearly identifying key community water needs as they relate to food production, animal husbandry, potable and daily household water use, and the size of the community that the resource supplies.

f. Sacred or culturally significant sites, environments, ecosystems that might be impacted or benefited by a MAR project should be clearly identified via community consultation.

g. Identical to the recommendation in Step 1, the collection of photographs is highly recommended unless there are cultural or social restrictions that may prohibit them.

Setting expectations is an important part of any community process. This is a cautionary note as it relates to managing expectations relative to the development of a MAR project. Being clear on expectations with an eye on ‘scalability’ of a new MAR site well help to maintain community engagement and ensure that any positive momentum generated by the first project can be leveraged to expanded and add additional sites.

Water Man of India

Rajendra Singh of India was named the 2015 Stockholm Water Prize Laureate, for his innovative water restoration efforts, improving water security in rural India, and for defeating drought and empowering communities through demonstrating courage and determination in his quest to improve the living conditions for those most in need. Learning how to harvest rainwater, cutting the peaks of water to fill the troughs, will be a key skill in most parts of the world. Two decades after Rajendra Singh arrived in Rajasthan, 8,600 traditional sand dams (johads) and structures to harvest river flows to recharge groundwater had been built. Water had been brought back to 1,000 villages across the state. Mr. Singh, his co-workers in Tarun Bharat Sangh (India Youth Association) had gotten water to flow again in several rivers in India’s Rajasthan region.

Stockholm International Water Institute[1]

Step 3: MAR Project Feasibility

Following the compilation of the biophysical and community information gathered during Steps 1 and 2, the feasibility assessment of the project can begin. This step assesses the potential risks of each potential project component relative to their intended benefits. For example, if potable drinking water supply is the goal, and the source water has high levels of bacteria in it, it is critical to ensure that the MAR technique being used will not accidentally increase the pollution risk for groundwater supplies. The goal of this step is to bring together the information gathered, look for any fatal flaws, and work to manage these flaws (through design) and/or consider how the project might be changed to focus on an alternative outcome.

A feasibility study can range from simple to highly technical depending on the information collected in the first three steps of a MAR project. However, it should be noted that MAR projects do not necessarily require a team of engineers or scientists to determine their feasibility and/or design and build a good MAR site and/or program (see the “Water Man of India” section below).

Water Man of India

Rajendra Singh of India was named the 2015 Stockholm Water Prize Laureate, for his innovative water restoration efforts, improving water security in rural India, and for defeating drought and empowering communities through demonstrating courage and determination in his quest to improve the living conditions for those most in need. Learning how to harvest rainwater, cutting the peaks of water to fill the troughs, will be a key skill in most parts of the world. Two decades after Rajendra Singh arrived in Rajasthan, 8,600 traditional sand dams (johads) and structures to harvest river flows to recharge groundwater had been built. Water had been brought back to 1,000 villages across the state. Mr. Singh, his co-workers in Tarun Bharat Sangh (India Youth Association) had gotten water to flow again in several rivers in India’s Rajasthan region.

Stockholm International Water Institute[1] [1] https://www.worldwaterweek.org/news/the-water-man-of-india-receives-stockholm-water-prize

Some of the key questions that a MAR feasibility assessment should cover are:

a. Is there a MAR technique that can be used to recharge a groundwater area or an aquifer that has a beneficial use for the community?

b. Is the source water suitable in quality, quantity, and availability for use in a MAR project?

c. Are the target aquifer(s) suitable for MAR and how much opportunity is there to improve groundwater for the identified beneficial uses?

d. Can the intended beneficiaries access the recharged groundwater in ways that are practical and cost effective?

e. Can the Mercy Corp team and/or community get access to any required technical support or specific infrastructure needs (e.g., borehole drillers and/or excavation equipment)?

f. Will recharging the aquifer have any detrimental effects on the quality or quantity of groundwater, sensitive environments, or cultural practices and values, and if so, what are they?

While there are any number of guidance documents for the development of MAR projects (an illustrative list is discussed in the MAR Project Resources section below), these are unlikely to be completely appropriate to any specific project, particularly those designed and implemented within Mercy Corps target communities. While some degree of improvisation is therefore required, the Technical Support Unit is available to help teams find appropriate sources and technical assistance as needs arise.

Step 4: Site Investigations

Field investigations are often used to collect site specific information on a MAR site during or after the feasibility assessment. This is particularly important if the project involves a complex design or there is an absence of key information needed to progress on a project (e.g., depth to a water table can influence the amount of storage available in unconfined aquifers). Site investigations can involve relatively simple tools and visual observations (e.g., digging down to the water table with a shovel and noting the soils, including confining or permeable layers of the hole) to more much more complex evaluations (e.g., drilling a test borehole to confirm a deep aquifer is present). One outcome of the feasibility study should be clear guidance on whether additional site investigations are required to move the project design forward. A combination of support from Mercy Corp staff reviewing the technical results should be coupled with a community-led assessment of the plan. Site investigations should be led by Mercy Corp staff and the local project champions.

Step 5: MAR Site Designs

The final designs for a MAR project should go beyond simple schematics and infrastructure components. A final MAR design should have a clear set of a goals that help manage expectations in the community as well as help to scale the final infrastructure and construction costs. There should also be explicit consideration of how the project(s) can be scaled to address the overall needs of the community. Clogging is a primary concern for any MAR project and final designs require evidence that this issue can be managed for the longer-term operations of the site. Costs, access to local materials, labor, and local expertise as well as managing any security or safety needs should also be incorporated into the overall project design. Ensuring that the local community is trained to operate and maintain the site is another obvious feature that needs to be covered. Finally, final designs should ensure adequate and ongoing monitoring for potential risks (water quality) and measurement of anticipated benefits.

Step 6: Construction and Operations

As with all engineered projects, the construction and operation of the final MAR site are key outcomes of all the preceding steps. If the final ‘as built’ layout of the MAR site is notably different than the designed site, updating the site information is often a good practice and can be incorporated into the final MAR operations information. Training local operators on site operations, maintenance, and any required monitoring is an essential part of community education and outreach. It is often best to clearly identify the local entities and/or champions that can be trained and subsequently pass down the knowledge to future operators in the community.

Step 7: Results and Adaptation

While MAR projects can improve groundwater security, more than one site may be needed to fix groundwater sustainability problems in a catchment and meet a community’s water needs. Leveraging the positive results from the initial demonstration projects is critical to developing new sites and building recharge processes up to the scale that is needed to support overall water security needs. Also, through operations, observations, and specific scientific monitoring (as needed), initial designs may be adapted to address the complexity of the groundwater system and spatial differences found across a catchment. Improved methods to reduce clogging and better deliver water to the target aquifer are also part of the scaling and adaptation process. Success also helps build community momentum, and projects that result in positive outcomes can be leveraged by the community to continue to access additional aid support and resources. It is recommended that a technical and community assessment take place once significant changes are in place (for example in one to three years following construction). Cycling back through this stepwise project should help when expanding the recharge program and helps to ensure that there is logical thinking behind the development of a catchment wide groundwater replenishment program.

MAR Project Resources

The International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre (iGRAC) based in the Netherlands has developed an interactive global mapping MAR Portal (Figure 6) that contains detailed information on over 1,200 MAR sites around the world as well as regional MAR suitability maps.[1] The site facilitates access to information and knowledge on how the various tools of MAR are being applied to water security and community resiliency and promotes international information sharing. The inventory contains information on site name, location, MAR type, year when the scheme came into operation, the source of infiltration water, the final use of abstracted water, and the main objective of the MAR scheme. Links to reports and resources are also available which can be helpful in gathering more detailed information on specific sites or programs.

The iGRAC MAR Portal also offers information on various initiatives in this field. For example, there is information on recharge efforts underway in the transboundary Merti Aquifer, shared between Kenya and Somalia. This is a joint effort of iGRAC and Acacia Water, commissioned by IGAD Inland Water Resources Management Programme (IGAD-INWRMP), an EU funded programme to strengthen capacities in the field of water resources management in the Horn of Africa.[2] This initiative also developed regional mapping of the potential of MAR and developed a Strategic Tool for Climate Change Adapatation (related to groundwater and MAR). Finally iGRAC has also developed additional information sources including: global maps of groundwater stress, groundwater resoures in Africa, groundwater monitoring network (GGMN) and country-specifc data on groundwater.

Figure 6. iGRAC MAR Portal showing a variety of MAR programmes around the world

The International Association of Hydrogeologists also have an excellent website which provides a wide range of information on MAR.[1] Resources include connections to various communites of interested practioners and researchers in a range of MAR fields such as: MAR for Sustainable Development, Economics of MAR, and MAR Regulations. Links to a range of other MAR related agencies, including UNESCO, can also be found at this website.

The International Water Management Institute has the most comprehensive online resources when it comes to water security and resilience for the developing world.[2] Particular to MAR, IWMI has developed the Groundwater Solutions Initiative for Policy and Practice (GRIPP).[3] The organization’s website has a wide range of key groundwater management ideas and tools including the case studies and examples that are shared in this guide. Their Groundwater-Based Natural Infrastructure (GBNI) provides an excellent resource relative to MAR for the purposes of storage, water quality, water retention (flooding) and environmental services. The list of partner organisations also provides access to numerous other data and technical information that can help Mercy Corp staff to further their understanding of groundwater solutions implemented around the world.

Finally, YouTube is also an excellent source of MAR project videos, especially relating to community-led projects in the developing world. Two recent videos from India, produced as part of the Paani Foundations’s Water Cup Competition merit mention (Figure 7). [1] The videos exemplify the community enagement and catchment-scale approach, as outined in this guide, as well as addressing a range of other issues including flood and drought management), erosion control, local leadership and the connections between permaculture, water security and community resilience.

· I

Figure 7. Paani Foundation ‘From Drought to Prosperity’ Videos explaining the development of a grassroots, groundwater replenishment program at the community-scale (2020, courtesy Andrew Millison – Oregon State University, Oregon USA)

[1] https://www.paanifoundation.in/ with the two you tube videos at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-8nqnOcoLqE and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jDMnbeW3F8A

Finally, Mercy Corps teams are also encouraged to contact the Technical Support Unit for additional resources and contacts.

CONTACTS/AUTHORS

Eliot Levine Director Environment Team Technical Support Unit elevine@mercycorps.org

Bruce Aylward Senior Advisor Water Environment Team Technical Support Unit baylward@mercycorps.org

Bob Bower Principal Hydrologist H2Alluvium BBower@H2Alluvium.co.nz

Mercy Corps

45 SW Ankeny Street Portland, Oregon 97204 888.842.0842 mercycorps.org

Comments